MMLU-Pro Isn’t Multidimensional (It Just Pretends to Be)

In this blog post, I do an open-ended exporation of the dimensionality of model capabilities captured in MMLU-Pro, and consider whether asking questions across domains might improve our understanding of model abilities. Using item response theory to analyze model performance, I find that

- MMLU-Pro tests a single-dimensional ability, despite asking questions across a range of domains.

- Questions from fields that are an even mixture of both qualitative and quanitative domains appear to be more difficult, but questions that are more quanitative tend to be the most discriminating.

I speculate about what this implies for the role of these kinds of evals in our model understanding and forecasting tool kits.

Motivation

Benchmarks have many uses. In my opinion, the purest of these is to measure progress towards AGI. For this use case, we often think the breadth of a benchmark makes it better. We build models that test across X many domains and take comfort in the idea that covering many fields gives us a richer picture of intelligence: this model is great at X1, X2, and X3, so it must be getting more capable in some fairly general sense way.

But that hypothesis only holds if the benchmark’s domains are actually measuring meaningfully different things.

A multi-domain benchmark can be broad in what it covers while being narrow in what it reveals. If performance is mainly driven by how good a model is at test-taking or memorization, then adding more domains doesn’t necessarily buy us a more articulated map of capabilities: it may simply average out noise around one dominant dimension.

On the other hand, if domains really do correspond to multiple capabilities, then our habit of collapsing eval scores into one metric is hard to justify. We would have to monitor how the capability profile is evolving over time.

Yet today it’s often unclear what we should even expect to see in either case, because we rarely make the underlying hypothesis explicit. Instead of treating “multi-domain” as automatically meaningful, I want to treat it as a claim about the structure of model intelligence—one that we can test, and one that should shape how benchmarks are built and reported. In this short post, I find evidence that the former is the case for MMLU-pro, a widely used and cited question answering benchmark.

Experimental setup

I use publically available MMLU-Pro data. This data evaluates 47 models across 12,032 questions. A benefit of using this benchmark over other is that MMLU-Pro classifies its questions into 14 domains: math, physics, computer science, engineering, chemistry, economics, biology, health, psychology, business, law, history, philosophy, and other.

To begin poking at these issues empirically, I use Item Response Theory. Unlike analyses applying Classical Test Theory where the total score is the main object and items are treated as mostly interchangeable, Item Response Theory models the probability of a correct answer as a function of both a model’s latent ability and each question’s latent properties. Using IRT, I’m able to see which items actually separate models and look at the dimensionality of model ability.

Limitations

The public data on MMLU-Pro is only evaluated on smaller models, and that even among these smaller models the benchmark is mostly saturated. This seriously limits my ability to extend ths conclusions of this analysis to larger models. I propose readers think of this more as a motivational exercise that can be applied to more state of the art benchmarks.

Results

Dimensionality

I use multidimensional item response theory (IRT) to jointly model subject-level performance and item characteristics across (D) latent dimensions. For each choice of dimensionality (D), the model defines:

-

Subject (ability) parameters: for each subject $s$, a vector of abilities $\boldsymbol{\theta}_s \in \mathbb{R}^D$.

-

Item parameters: for each item $i$, a vector of discrimination parameters $\mathbf{a}_i \in \mathbb{R}^D$, and a scalar difficulty parameter $b_i \in \mathbb{R}$.

I observe whether subject $s$ answers item $i$ correctly as a binary variable $y_{si} \in {0,1}$, and model it as:

\[y_{si} \sim \text{Bernoulli}(p_{si})\]where $p_{si}$ is the probability of a correct response.

In the multidimensional 2-parameter logistic (2PL) model, this probability is linked to the latent abilities and item parameters via:

\[p_{si} = \sigma\big(\mathbf{a}_i^\top \boldsymbol{\theta}_s - b_i\big)\]where $\sigma(x) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-x}}$ is the logistic function.

Given estimates of $\boldsymbol{\theta}_s$, $\mathbf{a}_i$, and $b_i$, I can compute the predicted probability that each subject answers each item correctly and compare these predictions to the observed outcomes. I fit models with different values of $D$ and compare their fit (e.g., using likelihood-based criteria or held-out performance) to identify the dimensionality that best captures the data.

In the following table, I find some suggestive evidence that MMLU-Pro might be one-or two dimensional depending on whether we look at AIC or BIC.

| Dims | Log Like. | Param. Ct. | Obs. Ct. | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D | -327446.22 | 24561 | 565033 | 704014.44 | 980194.02 |

| 2D | -236819.97 | 49122 | 565033 | 571883.94 | 1124243.12 |

| 3D | -220614.37 | 73683 | 565033 | 588594.75 | 1417133.52 |

| 4D | -249462.71 | 98244 | 565033 | 695413.41 | 1800131.77 |

| 5D | -215016.80 | 122805 | 565033 | 675643.60 | 2056541.54 |

| 6D | -243958.27 | 147366 | 565033 | 782648.54 | 2439726.07 |

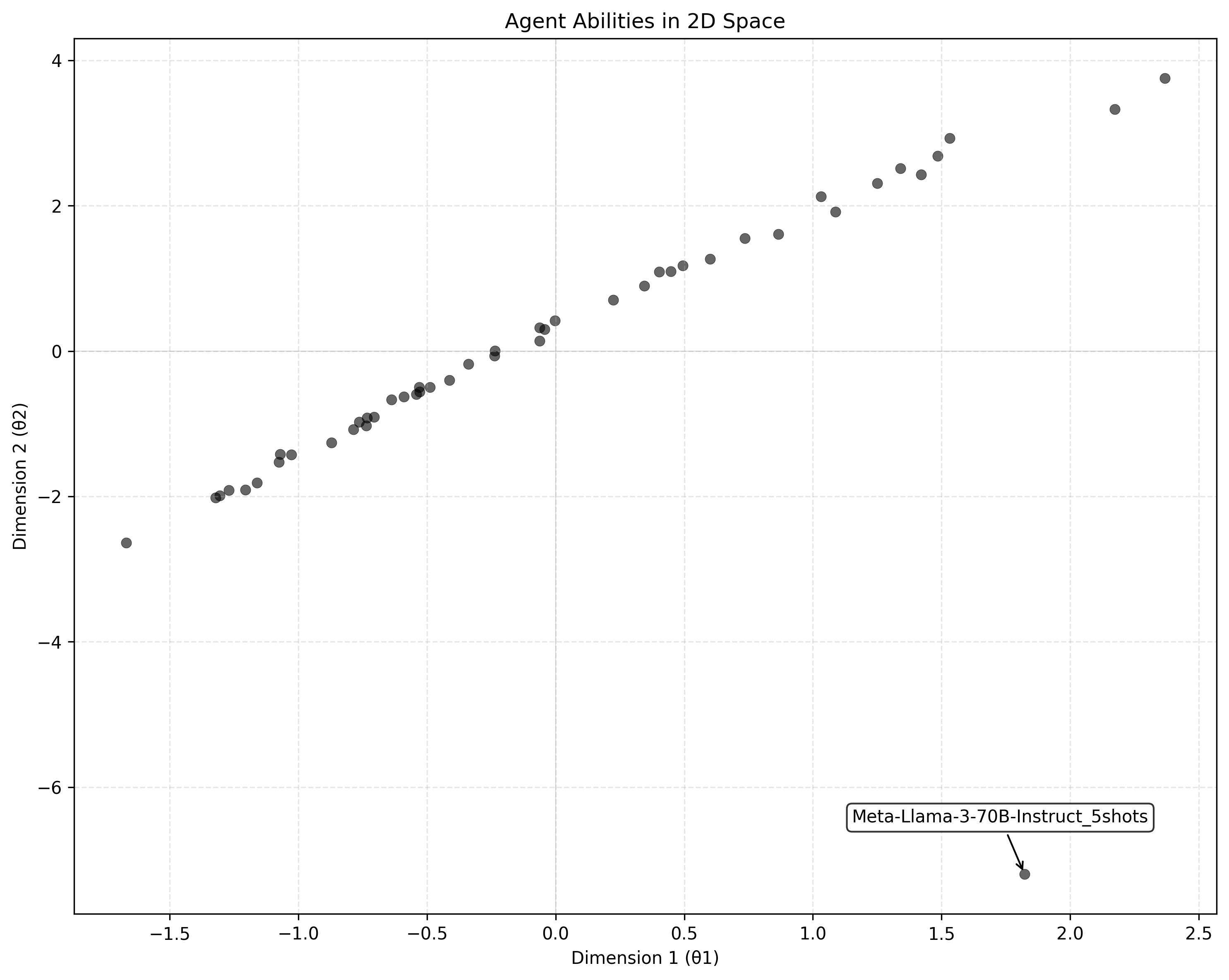

However, in the visual comparison of a model fit on one vs. two dimensions, I find that the second dimension is from overfitting on the Llama outlier.

Domain Differentiation

Given that MMLU’s domains are likely only testing one latent ability, it’d be useful to see which questions are more or less effective at such kind of testing.

To do so, I can perform exploratory data analysis on the difficulty ($a$) and discrimination ($b$) parameters I derived. To better compare domains, I choose loosely categorize the domains by how quantitative (in purple) and qualitative (in yellow) they are 1.

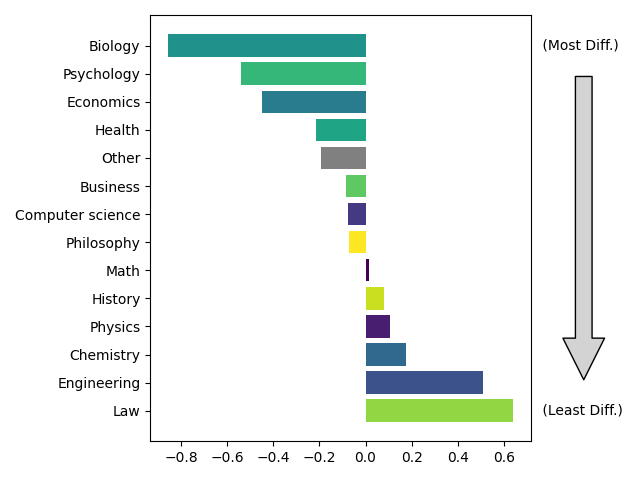

First, let’s look at the difficulty dimension.

Interestingly, the top few domains are considered to be in the middle of the road of the qualitative-quantiative scale. This classification seems reasonable to me: the top four fields – Biology, Psychology, Economics, and Health – are about the study of wrangling unmanageably complex systems into order by applying both quanitative and qualitative analyses. Though it seems unlikely to me that the quantitative-qualitative distinction is very helpful in determining why models find these questions more difficult. It seems more likely to me that questions from this field are more often steeped in the convention than ground-truth.

Depending on how dependable the qualitative-quantiative scale is, this might suggest that the one-dimensional “ability” being tested in MMLU is a kind of general integrated competence that arises when the models can combine both quantitative and qualitative skills. This might also suggest that, conditional on MMLU only being one-dimensional, that the benchmark could get the most bang for its buck by targeting questions in these fields.

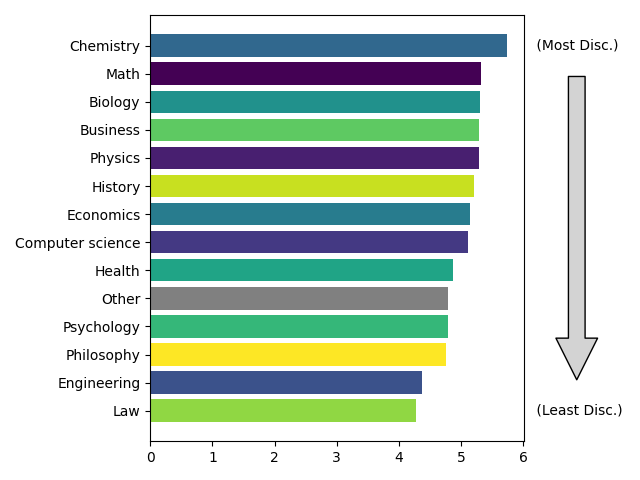

Next, let’s look at the discrimination dimension:

Unlike the difficulty parameter, the trends in discrimination are a less clear. It seems there’s a light correlation between more discriminating quesitons being more quantitative. The fact that the top four fields in terms of difficulty – Biology, Psychology, Economics, and Health – are scattered across the discrimination scale suggests these fields might indeed have more guess variation of ambiguous interpretation.

Conclusion

If MMLU is truly one-dimensional, the categorization of question across domains has less value: we’re paying the cost of multi-domain coverage without actually buying a more structured picture of capability.

To be clear, I’m not trying to say that multi-domain benchmarks are useless, but rather that we should be more explicit about these categorizations will do for our understanding. If the goal is to “track a single general competence over time,” then benchmark construction should perhaps optimize for items with high information, even if that means concentrating in the domains that empirically provide the most signal. If the goal instead is to “measure multiple capabilities,” then we shouldn’t expect domain labels to magically induce dimensionality, and instead design for them (i.e., by construct item families that isolate distinct skills and validating dimensionality with model-based checks on preliminary samples) and report by those sub-scores instead of collapsing into one general ability line.

Benchmark breadth should be informed by hypotheses about the structure of model intelligence, not an aesthetic choice.

---

-

I did this using ChatGPT 5.1 Thinking. Given that these domains are relatively broad and can easily capture a large range of questions, this categorization is very loose and only used for visualization purposes. That being said, they do correspond reasonably with my intuitions on which field are more technical vs. qualitative. To be more rigorous about this, I could have tried to categorize each individual question instead. ↩